What the Body Remembers

By Karthika Naïr

“Longing for tomorrow” also means a longing for new ideas. We asked important voices of the present to reflect on parts of our festival programme. Poet, fabulist, librettist, Karthika Naïr reflects on the belief that, since the dawn of humanity, dance has been a language and the body has a memory. However different the perspectives of the various choreographers in this year's program may be, they share these thoughts and you will find it in all their creations.

IN THE BEGINNING was the body, and the body was movement, and movement was life. Whether that body was of an amoeba, oak or angelfish. Zebra or zinnia. Movement, visible and otherwise, meant aliveness. Movement was also language, in that primeval age when words had not yet been invented, defined, catalogued. Early humans would not have been so different from – or perceived themselves as superior to – other animals: we too, as a species, conversed through elaborate gestural dialects that marshalled eyebrows and eyes, shoulders, hands and feet…

As Nicole Krauss reminds us through a magnificent passage in her 2005 novel The History of Love, we may be far less at home in our bodies thousands of years later, far less fluent in the lexicon of wrist and palm and fingers, far more prone to the “division between mind and body, brain and heart”. We may be far more subordinate today to the sophistication and sophistry of spoken/written languages (that inevitably became signifiers of country, region, religion, class, ethnicity… specific, often divisive, markers of identity).

But the body remembers.

And perhaps, traces of these age-old, unspoken, gestural codes – once humankind’s embryonic, imperfect and elementary, lingua franca – remain in our bone and blood, in the memory of cells. Perhaps, they still surge to the surface when emotions run too deep for words, or when we are startled out of our learnt verbal patterns comprising verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions. Every time we clap our hands in sudden joy, or press both palms together – with the fingers extended skywards – in salutation. Every time we nuzzle a lover’s wrist, the nape of their neck.

For the body remembers.

And from individual, once spontaneous, expressions of emotion grew other, more extended gestural phrases, entire embodied stories transmitted by one person, or two and three or twelve, by a collective or tribe: programmed movement we might today call choreography. Among ancient works of art uncovered across the planet are cave paintings of communal dancing — in places as far-flung as the Bhimbetka rock shelters of Central India (roughly 8000 BCE), at East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo (anywhere between 13 and 20 000 years ago), or those from the Round Head Period (7500-9500 BCE) at Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria. Dances to announce and commemorate births and deaths, harvest, a successful hunt… the moments that mattered the most; the moments shared in order to relish joy or make sorrow bearable. Moments that forged a community.

Which may be why, even today, there are occasions when we find people – many complete strangers, for once shedding centuries of acquired reserve and codes of propriety – coming together at life-changing or epochal instants to hold hands, swing hips and stomp feet in a seemingly unrehearsed yet blithely coordinated flurry of kinetic celebration. When a hard-fought battle for democracy is won, and citizens spill into the streets, gleeful and disbelieving that they have outlived oppression. When protracted droughts end with the arrival of long-awaited showers and the earth crackles at the graze of raindrops. Or when an underdog sports team triumphs – against all expectations – at a world championship!

Because the body still remembers.

So how did dance – this immediate, primal expression traced back to Neolithic Man – go from being the most demotic, the most accessible, of art forms to one increasingly perceived as elitist and abstruse, something removed from our realities, something, well, ungraspable? Was it when the instants of communal dancing became circumscribed by priests and shamans as a channel to the divine, with only a chosen few allowed to symbolise the collective, allowed to converse with, or appease, the gods through their dancing bodies, with those bodies then held to lifelong scrutiny? Was it when those in power realised that a moving, dancing, body was the very exemplar of freedom, and took to steps to have it regulated? Contained through conditions of entry and acknowledgement imposed by the arbiters of good taste; curtailed through rigid canons of beauty (Tall enough? Small enough? Fair enough? Bare enough? Slender enough? Tender enough?), with the honour of dancing for kings and courts dangled as reward?

Was it when colonial empires – not that long ago – established hierarchies of worth, of nomenclature: tribal, folk, traditional, popular, vernacular… overwhelmingly reserving the apex terms, the crown, of “classical” or “canonical” for genres from the majoritarian culture(s)? Words that in themselves would be innocuous if they had not been wielded to tremendous effect; words that have successfully created divides of high art and low art, often along the same lines of Othering that we have seen operate globally. To imprint, consciously or not, fear and shame, envy and inferiority and aspiration on the body is to colonise it. To imprint the unwritten laws on – quoting Mohamed Toukabri – who gets to move how, and why. And, of course, who gets to watch who, moving.

For the body, as Ta-Nehisi Coates posits[i], is the crucible of the soul and the spirit: reconfigure the soul’s vision of its own body, and control over both can be achieved. In the case of dance, that has granted control not only over the performer but also the viewer. Seen this way, the dancing body is a prime archive of centuries of colonial, imperial, and, of course, patriarchal, history. History that has impacted us all: coloured and white, queer and cis, marginalised and privileged... That observation is not an accusation; merely the reiteration of a fact, as much a fact as mountain glaciers being excellent chroniclers of climate change.

The body does not merely remember, fortunately: it resists, it reacts, it rallies.

And if dance was reduced, regulated, even instrumentalised, by various kinds of powers, we have witnessed a heartening rise of the subaltern within and through dance these last five decades or more. Choreographers and performers, dance communities, have seized the various kinds of Otherness projected onto our bodies – on to skin, hair, hips or voices – and are nudging us, urgently, unapologetically: Otherness is not a stain to hide, erase or endure; it is to be embraced. Examined, questioned. Perhaps this has always happened, this capacity of dance to subvert, to rebel. But in our times, yes, there has been a phoenix-like return of the marginalised through dance, and all across the world, like:

- In the near-miraculous – still precarious – revival of Robam Preah Reach Troap (Royal Ballet of Cambodia) that had been driven to near-extinction by the Khmer Rouge, with a vast majority of the exponents and instructors perishing – executed, tortured, starved to death in the labour camps – during the late 1970s under Pol Pot’s regime. Here is a story of resurrection catalysed in refugee camps and orphanages after the war.[ii]

- In the gradual reclaiming of centuries’ worth of tradition and knowledge by a new generation of dancers from the hereditary performing communities (often called Devadasis or temple dancers) of South India, a tradition they were dispossessed of when both colonial and nationalist forces implemented legislation across the 1940s abolishing the Devadasi system; laws intended to protect the women, but leading to their wholesale exclusion from the dances, particularly Bharatanatyam, and economic ruin.

- In the rise – and recognition – of a slew of street dance styles, from breaking and popping to waacking or voguing or house, first in America and now on every continent, most born in direct response to racial and gender-based discrimination and exclusion, beginning with their names: ‘street’ because African-Americans were not welcomed into dance studios, and ‘punking’ an appropriation of the very slur directed at gay communities.

Yes, the body remembers and (symbolically) resurrects. But the body, while resilient, is also vulnerable. And we live in an era of manufactured hate and fear, where violence as response to Otherness is surprisingly tolerated, even stoked, by authorities, by opinion-makers. There are all too many ways to shut down the body. Sticks and stones, as the saying goes — and guns and bombs, in all too many parts of the planet. But also bans and censorship. Accusations and rumours, shifts in public opinion, absence of funding. And, even in the most ‘developed’ of societies, that old insidious idea, that dance is not necessary, not directly relevant, to our lives. That it is, perhaps, only decorative.

Nothing could be further from the truth — as history and pre-history tell us, with those cave paintings that have outlasted every tyrant, every dynasty, every calamity. Dance, to borrow François Chaignaud, Nina Laisné and Nadia Larcher’s words, is a living canvas, reflecting and configuring (these) identities in the making: a canvas that recorded our past, and reflects our present. Its power lies in its very fragility, in its impermanence. Like calligraphy on water, it will only exist in the moment — except in our minds, its only real home. What a timeless, extraordinary ritual is performance. One that needs our bodies, our attention - of those who witness and absorb it – to carry it into the future, to tattoo its heartbeat into our memories. There is a reason, I reckon, dance is termed “spectacle vivant” in French: live art. It needs our breath, the breath of both performer and viewer, to breathe. That is the sacred covenant binding us together.

Let the body breathe, breathe to remember — and be remembered.

[i]Dancing in Cambodia and Other Stories, Amitav Ghosh, Ravi Dayal Pub, 1998.

[ii] Between the World and me, Ta Nehisi-Coates, Text Publishing, 2015.

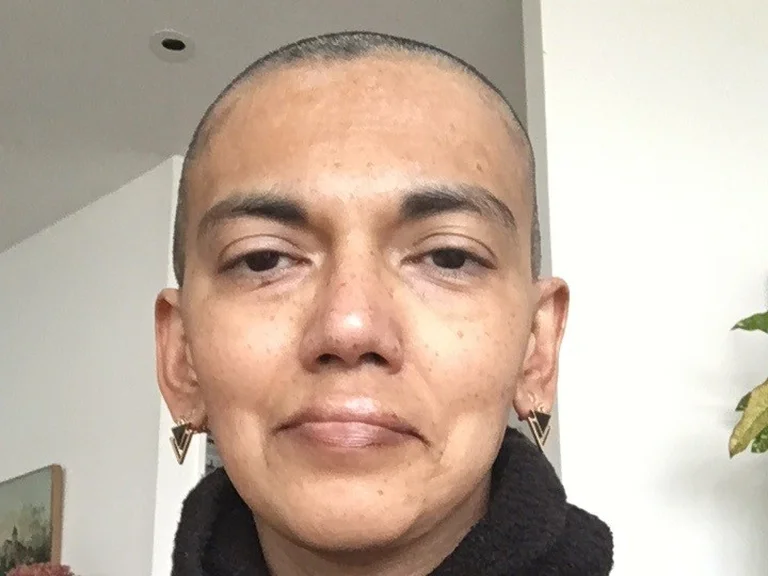

About the author

Karthika Naïr is a poet, fabulist, playwright and librettist. Her works include the multidisciplinary PETTEE: Storybox (co-written and co-directed with novelist Deepak Unnikrishnan), and the award-winning Until the Lions: Echoes from the Mahabharata. Naïr is the co-founder of choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s company, Eastman, and executive producer of several of his and Damien Jalet’s shows.